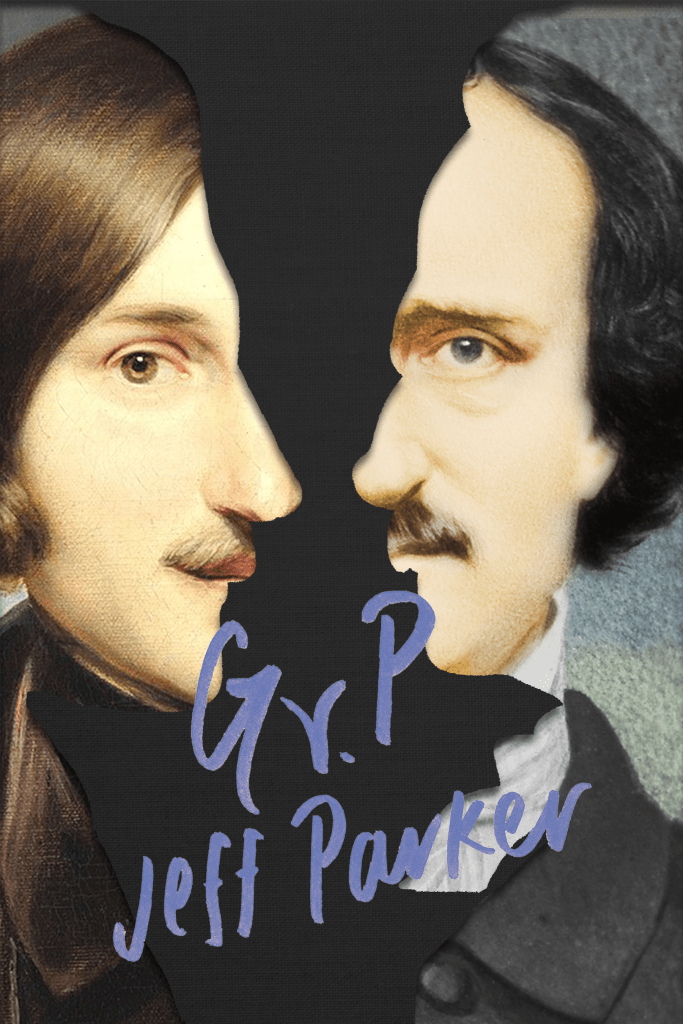

Proper Imposters – Forthcoming January 2025

Jeff Parker Interview

Grace Maxwell: How did the idea for G v. P come about for you—taking these two, tragic writers and putting them together?

Jeff Parker: Well, it was really through happenstance. I have long been a fan of Nikolai Gogol. He’s the reason why I first went to Russia, now some twenty—twenty-five years ago, and Russia became a big part of my life because of him, I guess you could say. (At least until recently, but that’s another story.) So, I had always been interested in Gogol, and, like a lot of Americans, I had grown up with Poe, but I didn’t actually know much about either of their lives.

My research started incidentally. I went to a play in the Berkshires about Poe’s life and learned about his very odd deathbed story. And it’s such a crazy story that it stuck with me. I later had occasion to visit the Poe house in Baltimore. Then I read a biography of Gogol, and I started to see that there were a lot of correspondences between the two men’s lives. Gogol has a very strange and macabre deathbed story as well, which we can get into. But the direct answer to your question is I just started to see all these similarities between them, and they were roughly the same age—I think they’re two years apart—they were born and died at roughly the same time within a couple of years of each other. One of the primary influences for both of them was a Prussian writer named ETA Hoffman, who a lot of people know through his works like The Nutcracker and The Sandman.

But at a certain point the connections between them become kind of eerie. It’s almost like they were destined to hook up. Gogol once, when he was a very young man, planned a trip to the U.S. And he actually made it most of the way across Europe. He was planning to take a ship from the U.K., but his neuroses got the best of him, and he turned back. He didn’t go. But there was that potential that he could have gone there, and they could have met. And then the unsavory gentleman who wrote Poe’s first obituary—and I should say that I’m not a Poe or Gogol scholar, this is all amateur research—but as I understand it, the guy who wrote the obituary was trying to build up Poe’s reputation even more. So, he basically wrote the obituary as a series of tall tales about Poe—who was, frankly, already a legend. But one of the tall tales that he invented was that as a young man, he had fought in a war in Greece, and then he had spent time in St. Petersburg, Russia. That was not true, but it was published in his obituary.

So, as a fiction writer, that just excited me about the possibility or the idea of the two of them meeting. And so, I just began to toy around with that idea. I’d write some pages here and there, goofy bits of dialogue about what they would say to each other riding on a train, and I was really doing it as nothing more than a gag to entertain myself, but eventually it started to accrue, and I started to think about it as something like a novella.

GM: That’s awesome. I love how you can find inspiration in the most random places. I think that also kind of answered my next question: who do you think is the better writer? But I’m thinking, it’s Nikolai Gogol, obviously.

JP: That’s a good question. “Who’s the better writer?” Well, Dostoevsky famously said that all of Russian literature comes out from under Gogol’s overcoat. But then, as we know, Poe is the inventor of the detective story; he’s the progenitor of the dark heart of American literature, let’s say. So, in terms of influences, I think it’d be really hard to say who is the bigger influence, or who had the bigger shadow. But personally, for me, Gogol had a much better sense of humor, and that wins the day. So, yes, I am in the Gogol camp.

GM: Yeah, I remember in the story Poe felt—jealous, maybe?—that Gogol was so much funnier than he was. So, moving on, why did you decide to only use their first initials in the story rather than their full names?

JP: It’s worth noting that if the designers hadn’t elected to put pictures of Gogol and Poe on the cover, I suppose it’s at least conceivable that people would read that [my story] without any awareness at all of those references. And I wanted that reading to be possible.

GM: So, that sort of leads into the theme of Proper Imposters, you know, the mysterious aspect. That’s really interesting. And speaking of the theme as a whole, I was talking to Professor Fink about how the whole book came together, and he said that you four authors just wrote on your own. And then, Panhandler saw themes connected throughout.

On the back of the book, it’s [the book] described as “Four contemporary authors explore the vices and virtues of deception and how it manifests in personal, psychological, propulsive, and profound. These novellas startle with the consequences of seeing and being seen.” I was wondering if you could speak to how your story in particular speaks to the consequences of seeing and being seen?

JP: There are obvious connections among the pieces in the book. They go together in surprising ways especially considering they weren’t intended to go together. I suppose the literary connections between mine and Chaya’s novella [Lalita] are maybe the strongest.

But I think it kind of goes back to the question that you just asked about. The real-life figures who those characters are modeled on obviously didn’t meet in real life, so the whole conceit of my book is a fictionalized imagining of a meeting that didn’t take place. It doesn’t take the approach of historical fiction, which would be to try and recreate those characters authentically. [In G v. P], they speak with a modern diction—it’s not a work of historical fiction. But I suppose it is a work about imposters in a thematic sense. I think that’s why it fits because those characters in that novella are imposters born of my imagination coupled with some amateur research into the biographies of those characters’ lives—it’s obviously not them, and that’s maybe all the more reason why they shouldn’t be named Gogol and Poe. It’s suggests that the characters might be them but leaves room for the characters to not be them, if that makes any sense.

GM: Yeah, absolutely. So, this next question can be broader, it doesn’t have to be specific to G v. P, but I would like to know what your writing process is as a multiple-times published author.

JP: Well, it’s very much like what I described to you that was the process that resulted in this novella. Usually, there’s just something that interests me. It’s more often something like a character who I’m interested in, or maybe it’s like a particular plot line connected to a character that I’m interested in playing out and running out. Sometimes, it can be as simple as a line that I overheard on the bus or at a coffee shop or something. But something gets me writing, something interesting to me, and usually—I consider this a good thing—I don’t have a strong idea where it’s going or what it’s going to become. But in doing the writing, you figure out those things. Writing, to me, is a process of not knowing and figuring out what happens next. And it doesn’t always work, but when it does work, usually a form is suggested. Is this going to be a short story? Is it going to be a novel? Is it going to be something in between, like this novella form? But I guess that’s the process—you start writing about something that you’re obsessed with or interested in for some reason, and you kind of try and follow it, in an honest way, toward where it wants to go. That’s what’s exciting about writing to me, figuring things out in that way and seeing what comes of it all.

GM: It’s interesting that you don’t write with the end in sight. Would that be accurate to say, that you don’t write knowing exactly where the piece is going?

JP: Usually. I feel like this work is a big exception to that because of—and maybe this gestures back to something that I mentioned in the beginning—their deathbed stories. I realized pretty quickly when I decided to stick with this and turn it into a book that the deathbeds would have to be the kind of frame for the story. I basically decided there’d be two elements to it: there’d be the deathbed frames, and there’d be the flashbacks to their travels together in the middle, the idea being like on their respective gruesome deathbeds the things that they both thought back to was this trip that they took together when they were young.

So, I did very much know where the novella was going to end—it was going to end with them expiring. I didn’t know at all where the trip was going to take them. I wrote several different drafts of the trip that were very different. Actually, having them meet in St. Petersburg was a very late addition, and I think I added it after I read that Poe obituary. But previously, I had them meeting at some port in Boston or Baltimore. But really, the heart of this book to me was their deathbeds; so, usually, I don’t see it coming, but here I knew it was going to be that.

And I just have to tell you about their deathbed scenes. I mean, you’ve kind of read about it, but they’re so horrible. Gogol lost his mind toward the end, and he was a major hypochondriac, and he was employing these medical wackos. They were primarily bloodletters, but they were basically killing him; they were starving him and draining him. Shortly before he died, he burnt the manuscript of the second book of Dead Souls, which was to be his magnum opus. And then, he immediately thought, once he did it, that the devil had tricked him into doing it. I had the opportunity to go to that house where he died in Moscow, and see that room, and see the fireplace where he burned the manuscript. That was very eerie, but I don’t know if it even compares to Poe’s deathbed story because Poe, as you may have gleaned from reading the book—well, no one really knows, actually, for sure, what happened to Poe, but what they know for sure is that he was found the day after election day in a ditch, wearing someone else’s clothes, and in a kind of catatonic state. One of the theories that scholars have is that he was picked up by this political group called the Plug Uglies, which had this, if I understand it correctly, they had this thing they’d do wherein they’d round up vagrants and they would pump them full of laudanum and essentially turn them into voting zombies. They’d drive around to the various precincts, and they’d send them into each precinct to vote as many times as they could by changing their clothes every time they came out and sending them back in. And so, the theory goes that Poe, who was a notorious alcoholic, was probably drunk and mistaken for a vagrant. He was really a celebrity then too, the most famous writer of the day. This is the thing that’s amazing about it too—to put this in a contemporary perspective, we’d have to imagine someone like Taylor Swift being mistaken for a vagrant and turned into a voting zombie and left in a ditch to drown. Someone later recognized him and got him to the hospital, but it was too late, and he died.

They both also had a deep fear, which was a pretty common fear at the time, of being buried alive. Gogol had actually drawn out some schematics of a coffin that would have a knocker or something on it that he wanted to be buried in. But death was obviously a big obsession for both of them, so the beginning and end of that had to be the deathbed stories. There was really no getting around that.

GM: Did you find the deathbed scenes easier to write or harder to write since you had a lot of outside information going into it? Did you feel that you had the liberty to diverge, since you said this is not historical fiction, or did you feel that made the writing tougher?

JP: I feel like I wrote those scenes fairly true to the material that I found about those episodes. Of course, I tried to project them pretty deep in character. I’ve had a couple of friends who told me they read it, and they didn’t understand what was going on there, and I’ve sort of thought maybe I wrote it a little bit too deep in character. Maybe I should have pulled back and had a bit more of an omniscient narration there, but I don’t know. There was something to just being deep in the character that seemed important to me, but I don’t know if they were harder or easier to write. To a degree, it’s a little bit easier because you have the rough contours, and you just fill in the characters’ experiences.

GM: So, this question is mostly for me, but in about the middle of the story, Gogol tries boiled peanuts, and he hates them. And I want to know, do you like boiled peanuts?

JP: I grew up in the south, not far from where you are, so I ate a lot of boiled peanuts as a kid, and they were very normal to me. And I love them because they’re basically, like, a salty snack that are like chips or something. But when I moved out of the South, and I would talk about boiled peanuts, I would realize how strange that seemed to people because people outside of the South don’t eat boiled peanuts. So, my relationship with them took on a different meaning. I like them, but I can also see how it’s very weird to people. Do you like them?

GM: As a kid, I didn’t, but I do now. I grew up in the South, and I took a little bit of offense to Gogol’s hatred of them—it was so strong—but I get it, too. It’s a Southern thing.

JP: It’s hard for me to say what that’s born of—how that scene manifested. That does feel to me like one of the iconic scenes in the book because there are basically three purveyors there: someone selling boiled peanuts, someone selling oranges, and someone selling wooden ducks. And I really pictured how in the South, you’re out on the highway out in the middle of nowhere, and you’ll have a few little stands there like that. That feels like a very familiar thing to me from growing up down there.

But I’m not exactly sure why that scene manifested like that. I know when I went to Russia I definitely had the experience of encountering foods that people love there that were abhorrent to me, like holodets, “meat jelly,” which is like a holiday snack there—everyone loves that. I couldn’t stand it. But maybe I was thinking of an inverse of that, I don’t know exactly. But I did like imagining the scene because Gogol was what we would call a foodie nowadays; he was very serious about food. So, my assumption is that he’d just be horrified by boiled peanuts.

GM: I love the line, near the end of their journey, that said G ate everything, and P drank everything in sight. I thought that line characterized them both really well.

JP: Maybe it’s that bit that best sums them up.