Seth Brady Tucker‘s third book, The Cruelty Virtues, will appear through 3: A Taos Press in January 2026. He is the executive director of the Longleaf Writers’ Conference and he teaches creative writing at the Lighthouse Writers’ Workshop and is an award-winning professor at the Colorado School of Mines near Denver. He is the author of the award-winning poetry books Mormon Boy and We Deserve the Gods We Ask For, and his poetry, fiction, and essays have recently appeared in the Los Angeles Review, LitMag, Driftwood, Copper Nickel, the Louisville Review, Post Road, and the Birmingham Poetry Review, among many others. He is originally from Wyoming and once served as an Army Paratrooper with the 82nd Airborne in Iraq.

Five Questions with Seth Brady Tucker

1. The natural world is portrayed in The Cruelty Virtues in different poems as a threat or consolation or both simultaneously. How do you view the natural world and your (or humanity’s) place in it?

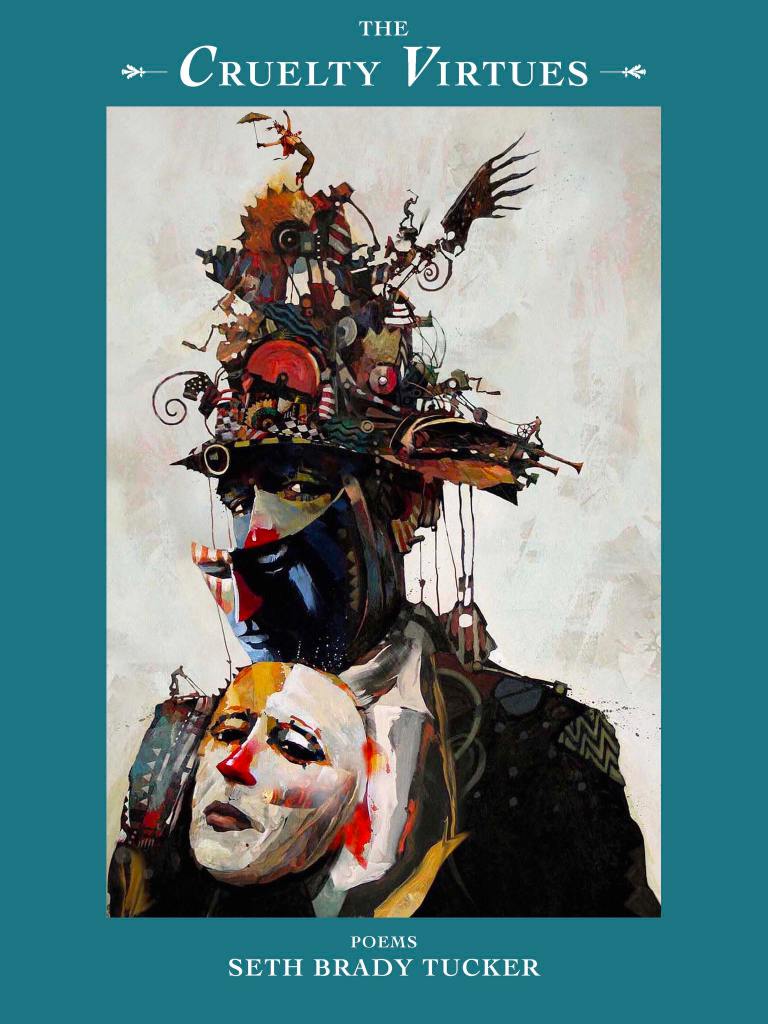

As I was writing this collection, there seemed to be this clear connection developing between the way our politics and our view of the natural world were colliding; the flawed and narcissistic marketing of ‘alpha male’ dogma focused its attention on the wokeness of environmentalists and naturalists alike and I couldn’t help but see how the man using a spray-gun to kill with pesticides and herbicides and fungicides was as violent in action as the man open-carrying in a supermarket. To me, these efforts to challenge nature or control nature clearly come from the same foundational beliefs, and most recently it seems to result in a need for men to deploy ‘masculinity signals’ to mask their own fear in much the same way that bees do it to signal who to kill. It is one of the reasons I was also drawn to the artwork of Bruce Holwerda and in particular my cover-art piece; I love the constant masking and unmasking his artwork shows us, and I know that so many men feel they must subscribe to this ‘doubling’ in order to protect their true identities. In the end, I don’t think this need to subsume or control nature is new, obviously, but it does seem to go hand in hand with the new dogma we are seeing with the Trump administration; that we must square the corners of the natural world in order to feel safe.

2. Several poems in the collection convey scenes of a speaker filled with love (for beloveds, family, those observed, humanity), and the depth of that love sometimes also produces trepidation in the speaker. I found myself thinking of the line in the hymn “Amazing Grace”: “It was grace that taught my heart to fear.” Is the consequence of devotion and love here in these poems an awareness of vulnerability/threat as well?

I agree with that and thank you for the reminder of that wonderful line—I’d forgotten it existed—but yes, I think as I’ve aged I’ve become more and more aware of what profound good fortune I have been ‘graced with’ when it comes to love and friendship. It wasn’t always this way. I left what felt like a very loveless home and a loveless faith when I left Wyoming and Mormonism for the military, and my time in the Army’s 82nd Airborne Division didn’t necessarily teach me to love with a full and charitable heart. If you can believe that! But I do think that art and the pursuit of writing poetry and fiction (and reading it as voraciously and enthusiastically as I have been able to do as a student and educator) have given me insights into how I was raised and how my own biology fires sensually and spiritually and emotionally when faced with complicated social issues. All that said; I feel like fear is the driving force behind nearly all the hate and rage and posturing anger we are seeing these days, so I work hard to know the difference between thoughts and actions that are generated by love and grace, and those that are based in selfish fear or jealousy.

3. I enjoyed the reality of the poems about the lives of soldiers and the lingering effects of Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan upon return. Tim O’Brien begins Going after Cacciato with an epigraph for Siegfried Sassoon: “Soldiers are dreamers.” Yet the soldiers here are very grounded in the materiality and sometimes disillusionment of return. Do you agree with Sassoon and O’Brien that soldiers are dreamers? Is there something about the requirements of being a soldier that necessitates dreaming?

I think there are service members and veterans who are dreamers, but I worry that they may be a dying breed. It is hard to dream when one has no sense of what is worth dreaming about, after all. Our recruits are generally less educated than ever because our education system consistently fails them, and they are poorer because our obsession with stock price means that any available jobs (and our wealth distribution system) is failing them as well. We have always fought our wars with the youngest and poorest and least educated, which ensures that they don’t know yet what they don’t know. So what dreams are possible when many cannot even conceive of a future without a weapon in their hands? Perhaps I am being cynical, but our military has lost their identity in the last fifty years, which means our recruits are less likely to understand who the enemy is than any other ‘war generation’ and that means they are more desperate, less likely to consider consequences, etc. But maybe there will be a new generation ready to challenge this and so maybe I am speaking out of turn. If I speak only for myself on this topic, I would admit that my ability to find dreams during and after my enlistment always featured some new knowledge or some new concept. I was lucky enough to be able to find a way to go to college, and I worry that there are fewer and fewer avenues for these young men and women to find and investigate complicated and nuanced concepts.

4. The Cruelty Virtues is your third collection. In what ways do you find your poems opening into new emotional or aesthetic spaces as you write now? Has your understanding of risk when writing a poem changed over time?

Yes, absolutely. It is one of the wonders and virtues and entitlements of being allowed to age and grow alongside our poetry. I can still look back at Mormon Boy and be proud of the earnest truths I was grappling with, but I also see the flaws. The same thing is true for We Deserve The Gods We Ask For; that book wrestled with the aftermath of war and asked the reader to consider heroism writ large, but there are poems in that collection that I wish I could edit. Our literary and publishing culture sometimes doesn’t allow for that kind of slow growth. In my mind, it is rare to find a twenty-something who truly understands poetry at a level that would indicate they have full mastery of the genre and form, but many are ‘anointed’ right out of the gate and then they have to live with a crown that must feel exceedingly heavy and awkward and fragile. Established poets know that the craft of poetry is a lifelong pursuit—yet our institutions treat emerging poets now as established masters of form—yet so many of these voices are just starting to discover what kind of poet they are going to be. How do they do that if they are judged by one poem or one book? I absolutely loathe the ageist awards we see flaunted around these days, and I believe that many of these young artists fade away or founder in their art because of this (unfair) early recognition. In some ways, a slowly building recognition around my work has been a blessing and I try to keep that in mind when I get frustrated with these institutions or when I feel like I am being ignored.

5. As a teacher of creative writing and a co-director of a successful writers’ conference for many years, what has captured your attention most when looking out at the contemporary literary landscape?

I think it is the fact that we still have young people falling in love with writing even though the world is communicating to them that it is useless or unnecessary. They have had so many negative platforms they’ve had to learn to manage (alongside those big cultural shifts thrown at them constantly through social media). They are growing up during a time of banned books, the anti-intellectual movement, and now generative AI, and yet they still find art. It is truly heartening and something I try to keep in mind as I teach. One of the main reasons Matt Bondurant and I worked to create Longleaf Writers Conference and Retreat was to ‘pay back’ in some way; I know I was so blessed to have great professors and mentors throughout my graduate studies and when I was able to attend conferences like Bread Loaf and Sewanee on scholarship it opened my eyes to new possibilities. I was always a late bloomer, so working with Ellen Bryant Voight and Phillip Williams and Reginald Dwayne Betts and others at Bread Loaf very literally changed my life and art. We figured that if we could give veterans and teachers and under-represented voices that opportunity in return? Maybe our Longleaf scholarships and fellowships could change the world, right? Just one artist at a time? My hope is that we give these young people the confidence and assurance that art does save us. No matter what the rest of the world may tell them.

Excerpt from The Cruelty Virtues

Song for the Dying of the Susans

They are born as teens without labor

unions or hard-hats—sent buzzing alone

into the wide sky like explorers without

supplies enough for the trip back; they

are bumblers of fate, holy managers

of pollen, they are fur-cloaked messengers

to those gods who measure value in the number

of wingbeats. We cannot know if their tongues

or wings will return soaked in poisons bio-engineered

for the beer-swilling Misters of pesticide & herbicide

clouds, but we pray for them if we must pray. We call

each of them by the collective name of Susan as

they bonk into our faces and shoulders before wilding

into the sky, they buzz upon thirsty desert lawns,

dodge cars & cats & bug Swatters & they drink

nectar that is filthy with poisons. The Susans

are brave in the manner of martyrs, & they give

& give & give & they tick the last days of their

lives out in clumsy wingbeats. Their men roam

the hive explaining how to be tender with sad romps

along petal & stamen & thorax. Most Susans return

weakened with mites & new bio-curses, & if they carry

death for their city poisoned in their blood? They will

turn away from their sisters, pedal their dying wings

to soft shorn grasses in yards or parks where they hum

with the last shiver of their sacrifice, glistening

their dying eyes into the sun, stilling their hearts, refusing

to harm even the families they will never meet.